User:StephanieVento/sandbox

Biological Resilience[edit]

Biological resilience is the theory that a person’s resilience is an inborn trait that is passed to them through genetics.

The most recent research on the development of resilience is divided between nature and nurture. Many researchers’ evidence suggests that resilience is the result of genetics and biological functions. Researchers Waaktaar and Torgersen studied twins raised together in the same household in order to evaluate the genetic and environmental influences on resilience. Both twins and their parents were required to evaluate the twins’ resilience in coping with their daily lives by filling out a questionnaire which assessed resilience via the Ego-Resilience scale. Through these surveys, the researchers were able to conclude that “just about one quarter of the total variation in trait resilience was attributable to environmental factors."[1] This provides evidence for the argument that while there are environmental influences on resilience, resilience is largely genetically predetermined; however, this was a study that focused on an everyday working definition of resilience rather than resilience in the face of trauma.

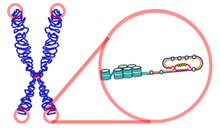

Other proponents of the biological theories of resilience chose to study the effects of telomere length on resilience. Because telomere length is related to physical decline brought on either by aging or stress, researchers wanted to see how it could be related to resilience. By studying the resilience of female rape survivors in relation to their telomere length, researchers found that shorter telomere length could be an indicator for PTSD risk and therefore would be associated with lower levels of resilience.[2]

Through the comparison of the genotypic information of maltreated and non-maltreated children, psychologists were able to study the effects of environment and genetics on resilience levels. Researchers identified the subjects’ different genotypes, divided them into groups based on this information, and then compared the resilience of the children in each group. Resilience was evaluated based on the coping and functioning of the children in relation to the standard for normal and healthy functioning for children their age.[3] By comparing the resilience and the genotypic classification in maltreated children and nonmaltreated children separately, the researchers were able to identify the genetic and environmental influences, and therefore determined that resilience is determined by the interaction between genetics and environmental factors, and it cannot be explained by one or the other on its own.[3]

Although this research is still in its early stages, it provides evidence to suggest that resilience could possibly be affected by genetics, and it generates enough interest in this possibility to propel further research on the topic.

References[edit]

- ^ Waaktaar, T., & Torgersen, S. (2012). Genetic and environmental causes of variation in trait resilience in young people. Behavior Genetics, 42 (3), 366-377. DOI: 10.1007/s10519-011-9519-5

- ^ Malan, S., Hemmings, S., Kidd, M., Martin, L., and Seedat, S. (2011). Investigation of telomere length and psychological stress in rape victims. Depression and Anxiety, 28 (12), 1081-1085. DOI: 10.1002/da.20903

- ^ a b Cicchetti, D., & Rogosch, F.A. (2012). Gene x environment interaction and resilience: Effects of child maltreatment and serotonin, corticotropin releasing hormone, dopamine, and oxytocin genes. Development and Psychopathology, 24 (2), 411-427. DOI: 10.1017/S0954579412000077

U.S. Veterans of the Vietnam War[edit]

In June of 2012, a group of psychologists published their findings from a 37-year longitudinal study on the resilience of Vietnam War veterans who were formerly prisoners of war. They were subjected to “prolonged captivity, malnourishment, and physical and psychological torture."[1] These researchers defined the term resilience using George Bonanno’s idea of resilience as an outcome, or “an individual’s ability to maintain stable psychological and physical functioning when exposed to an isolated traumatic event such as the death of a loved one or a life-threatening situation."[1] The study compared multiple variables with whether a subject was deemed resilient or non-resilient. To be considered resilient, a subject could not have been given a psychiatric diagnosis during the thirty-seven years that the study ran. Each participant’s resilience was compared with their optimism level, age, status (officer/enlisted rank), solitary confinement duration, PTSD symptoms, and psychopathic deviate (pd).[1] The researchers found optimistic participants were five times more likely to be resilient than subjects who were not optimistic, and officers were five times more likely to be resilient than enlisted soldiers.[1] They concluded that a participant's optimism and age at the time of their capture were the most significant factors predicting resilience (participants who were older at the time of their capture exhibited more resilience.)[1] Based on this finding, they went on to suggest that because optimism is the strongest predictor that can also be influenced and altered, it should be the focal point of therapy treatments to increase resilience. If a person is taught how to be more optimistic, they argued that the person would likewise become more resilient.[1]

References[edit]

Telomeres and Resilience[edit]

Recent research has linked telomere length to psychological resilience by studying the resilience of female rape survivors in relation to their telomere length.[1] Psychologists evaluated sixty-four South African female rape survivors immediately after the traumatic event (within three weeks) and again after three months in order to assess their mental health and coping abilities.[1] These evaluations were then compared to their telomere length measurements, and the researchers found that shorter telomere length could be an indicator for PTSD risk and therefore would be associated with lower levels of resilience.[1]