User:Paraskevia8/Sandbox

| Author | Elisabeth Reichart |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Georg Eisler |

| Country | Austria (Original) United States (Second Edition) |

| Language | Austria (Original) English (Second Edition) |

| Genre | Psychological novel |

| Publisher | Adriadne Press |

Publication date | 1989 |

| Media type | PrintPaperback) |

| Pages | 162 pages |

| ISBN | 0929497-02-3 |

The novel February Shadows (also known as Februar Schatten) was written by author and historian Elisabeth Reichart in 1984 as a response to her discovery of the tragedy of Mühlviertler Hasenjagd (The Rabbit Hunt of the Mill District). On February 2, 1945 almost 500 prisoners escaped from special barracks number 20 of the Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp in Upper Austria only to be hunted and killed by the inhabitants of the nearby village of Mühlviertler. All the villagers were instructed under Nazi command to find every escaped prisoner and either bring them to authorities or murder them immediately. The result was a bloody massacre involving previously "unpolitical" civilian men, women, and children.

February Shadows is an historically accurate fictional novel that explicitly depicts the event of Mühlviertler Hasenjagd through the eyes of a young girl named Hilde. The story is told in hindsight as Hilde is reaching back through repressed memories at the prompting of her adult daughter Erika who wishes to write about her mother's experiences. The book is essentially Hilde's silent inner monolgue as she struggles with her traumatic past and scarred present.

The story is not written in a traditionally chronological manner, nor does it conform to the rules of traditional grammer or sentence structure. The use of fragmented sentences and stream of consciousness allow the reader to better understand the psyche and experiences of the protagonist while reading the plot.

Plot[edit]

The story begins with Hilde awaking in the middle of the night to the sound of her telephone ringing. Upon answering she discovers that her husband, Anton, who was staying at a nursing facility for a severe illness has passed away. His death triggers feelings of loneliness and abandonment along with painful memories of the death of her older brother Hannes. Her daughter Erika, who is also present when Hilde receives the phone call, begins to cry for her father. Hilde becomes impatient with Erika; hinting at the continual and thematic strain of their relationship. The absence of Anton sends Hilde into a state of panic and despair.

Each day Hilde visits Anton's grave mentally talking to him as if he is still alive. One evening as she is returning home she discovers that a black cat seems to be following her. The cat causes her to remember two distinct experiences from her past. The first is a memory from when she was a small child and had attempted to hide a stray cat in her bedroom. Her family was very poor and could not afford a pet, but she saved her table scraps for it anyway. One day as she was coming home her father met her drunk in the doorway. He informed her that he had snapped the neck of the cat and then beat her harshly with a fly swatter. This first memory seeped into the second. She then remembered her daughter, Erika, begging to keep a stray cat she had found. Anton had granted her wish, but the cat ruined the neighbors' gardens and Hilde was forced to drown it in the river.

The following day Mr. Funk, a friend of her husband's, appears at her door and pressures her into joining the Retiree's Union. She joins because Anton had been a member of the Austrian Socialist Party and he would have approved of her socializing with other members. She assured Mr. Funk that she would attend the next evening social. Mr. Funk's visit forces another memory to resurface. She remembers her daughter asking what party Anton had belonged to during the period of National Socialism; Hilde recalled him being part of the Hitler Youth. The reader also discovers that Hilde's brother, Hannes, was killed by the Nazi Party. Erika's insolence upsets Hilde greatly.

Soon after, Erika calls stating that she will be coming to visit. Hilde wants to be with her daughter, yet she feels as if her daughter is a total stranger. Erika acts boldly and actively pursues her career as a writer. Hilde believes the only reason Erika wishes to come home is to get information for her book. Hilde hates relaying her past experiences to her daughter; her childhood was full of poverty, loneliness, and shame. Anton had been her way out of the past, and she only wanted to move forward; she was angry at her daughter for forcing her to relive it.

Hilde attends the Retiree's Union social only to find herself pretending to be happy. She watches the dancers on the dance floor and mourns the absence of her husband. The dancers trigger another memory from her childhood. She sees her father kicking her mother on the dance floor; she runs out to help. Soon both she and her mother are being beaten on the ground. Her father will not even let them comfort eachother. The only person she has to turn to is her brother Hannes. He comforts her. The memory is too painful for her and she leaves the social immediately.

Erika arrives the next day and announces that they will take a trip to the "village" so she can obtain more information for her book. (The reader must assume that the village is Mühlviertler.) Hilde does not wish to go, yet does not want to be excluded. As Erika and Hilde enter the village Hilde recalls working hard in the fields to harvest the crop the farmers left behind in order to have enough food for their large family. She remembers the hunger pains and how her father could not find work. She remembers Fritzi, a member of her apartment-style household, bringing eggs and bacon on sundays from the farmers and how she had felt proud carrying the basket into the kitchen. She had wanted her mother to be more proud of her than she was of her older and prettier sister Monika.

Hilde sees the lifeless and leafless pear tree in the village. She refers to it as the "February Tree." The tree that Hannes had been killed on. She remembers a Nazi in a black uniform telling her at school that her brother was dead. She remembers running through the snow and losing one wooden shoe in an attempt to save him. She remembers discovering he truly was dead and laying in the snow hoping for death. She and Erika visit her old house and she recalls beatings; they then visit the pond where she is reminded of the many loads of laundry she was forced to do alone with her mother. She begrudged her brothers who were not forced to do work, her oldest sister, Renate, who lived with their grandparents, and her delicate sister Monika who was never asked to manage hard labor. They walk down the lane to the old school lined with apple trees; she recalls the rough feeling of cobblestones on her sore feet and the bitter taste of the small apples. She also evades a certain barn on the lane, and avoids looking out into the distance towards the area which once held the Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp.

Upon returning to their hotel room Hilde reflects on her daughter. Her inner thoughts display envy toward Erika's privilege to be educated and to choose her career. Hilde reveals that she had always wanted to be a nurse; however her dreams of a nursing career were shattered the day her village was bombed during air raids; she watched her brother Stephen die as she was swallowed by mounds of earth. The raid had made her weak and incapable of dealing with trauma later in her life.

Eventually during their stay in Mühlviertler Erika is able to extract information about the fateful day in February that Hilde had been pushing from her memory for many years. Hilde relays that in the middle of the night she and her siblings were awoken by the sound of sirens. Her parents and the other tenants of her home were forced to hold a roll call in which Pesendorfer, the nazi authority in their house, told the tenents that many Russian convicts had escaped from the nearby concentration camp. He explained that it was their duty to Germany to find and kill each of these convicts. Hilde, being a young girl, is told to stay at the house; however she is worried about protecting her brother Hannes (who, like her other brothers is forced to search for prisoners) and sneaks away to find him.

In her search she comes across the barn near her school house. She enters it only to find that Pesendorfer, her neighbor Mrs. Emmerich, and her brother Walter all violently killing prisoners. She runs home and finds Hannes who informs her that he has hidden a prisoner in his wardrobe and that she must remain silent about it.

The next morning the villagers attend church to commemorate Candlemas. The hunters seek purification and are urged by their pastor to side with Germany and continue the search for the prisoners. At this insistence Hilde finds herself telling Hannes' secret to her mother. The story is vague about how this information is relayed to Pesendorfer, however he finds the prisoner, kills him, then takes Hannes away to beat him for his misconduct. Hilde recalls cleaning the blood from her brother's face after the beating. The following day she finds that Hannes has been hanged for his actions. Her guilt in the causation of two deaths is evident through her narration.

Back in the present day Erika is stunned by the horrific story and deeply regrets forcing her mother to relive the event. The novel closes with the image of the mother and daughter driving away from Mühlviertler with Hilde at the wheel and her foot on the gas pedal.[1]

Characters[edit]

Hilde: the protagonist of the novel. She is an old woman who witnessed Mühlviertler Hasenjagd as a young girl and attempts to evade all memories of the traumatic event.

Anton: husband to Hilde. He is the stable force in Hilde's life.

Erika: daughter to Hilde and Anton. She is a writer who wishes to create a novel about her mother's life experiences during World War II.

Mr. Funk: friend to Hilde and Anton. He is in charge of the Retiree's Union in their housing complex.

Hannes: brother to Hilde who is executed by Nazi soldiers for his attempt to save the life of an escaped prisoner during Mühlviertler Hasenjagd.

Father: father to Hilde. He is a poor, drunk authoritarian who abuses Hilde throughout her childhood.

Mother: mother to Hilde. She is a weak figure who turns a blind eye to the abuse inflicted on Hilde by Father.

Fritzi: neighbor to Hilde. She is a friend who is sent to labor for another farmer in order to obtain food for the poverty stricken household.

Max: brother to Hilde. He is married to Fritzi.

Stephen: brother to Hilde. He is killed during the bombing of the village during the war.

Walter: brother to Hilde. He murders an escaped convict during Mühlviertler Hasenjagd.

Monika: sister to Hilde. She is a delicate girl who is unable to handle the stress of the war and perishes in her sleep.

Renate: sister to Hilde. Hilde speaks little about her except to mention that she lived with their grandparents.

Mrs. Roth: neighbor to Hilde when she is an adult. She comforts Hilde shortly after the death of Anton.

Anna: friend to Hilde. She meets Hilde as a child, but they discover eachother later as adults.

Mrs. Emmerich: neighbor to Hilde. She murders an escaped convict during Mühlviertler Hasenjagd.

Pesendorfer: neighbor to Hilde. He is the nazi authority in her childhood home.

Mrs. Pesendorfer: wife of Pesendorfer.

Mrs. Wagner: neighbor to Hilde.

Mrs. Kal: neighbor to Hilde.[2]

Major Themes[edit]

Psychological Effects of Mühlviertler Hasenjagd[edit]

February Shadows can be categorized as a psychological novel. The entire narration is told through first person stream of consciousness, and the plot builds through the unearthing of new memories as they emerge in Hilde's mind. The story is told in a mix of past and present tenses and the narration switches fluidly back and forth between the two. The manner in which the flashbacks occur and the inner comments Hilde makes about each memory informs the reader that Hilde's main goal throughout the novel is to repress the horrific memories of February 2, 1945. Hilde constantly reminds herself throughout the book to forget the past; her survival and sanity seem to depend on it.[3]

Guilt has a great impact on Hilde throughout her life. She feels exteme guilt about the night of Mühlviertler Hasenjagd and remains haunted by the words of Hannes throughout her adulthood. "'Everyone,' he said then, 'who doesn't do something against this manhunt makes himself GUILTY.'" [4] Not only through ommission does she feel regret for the massacre, but she holds herself personally responsible for the deaths of the escaped prisoner and of her favorite brother, Hannes. Her guilt plagues her throughout the novel.[5]

An important psychological affect on Hilde was the coercion to embody the patriarchal fascist belief system of the time and to inculcate it into her own personal identity.[6] She was made to feel inferior and submissive, but also encouraged to never exclude herself from a group. This personal type of fascism aided in the rally of Austrian youth to support the Nazi cause during Mühlviertler Hasenjagd. Many years after the period of National Socialism it was still difficult for Hilde to extricate herself from this pattern of thinking. As an adult she still felt extreme anxiety about being excluded from groups and events.[7]

Dysfunctional Family Life[edit]

A very important theme about family, or lack thereof, is intertwined throughout the story in both Hilde's childhood and adulthood. Hilde's childhood is laden with abuse and patriarchal superiority. This is evidenced through her fathers harmful actions and also through her mother's unwillingness to ask her brothers to do housework.[8] In the ideal fascist society the family unit mimicked the hierarchical structure of the state.[9] In Hilde's case the state was stronger and more stable than her own family unit. This is evident at the climax of the novel when she is having an inner struggle about choosing to do what was right by Germany's standards or by Hannes' standards. In the end she chose Germany; her family life was too weak and dysfunctional to stand up to the instilled belief of Germany and the only morals she was aware of were the ones taught to her by the state.[10]

Though her married life was much better than her childhood there was still an aspect of inhibition in Hilde's ability to function as a normal family member. She constantly felt as if her husband and her daughter were purposefully leaving her out of conversations because she was less educated than they were and Hilde resented the exclusion.[11]

The Mother/Daughter Relationship[edit]

The Mother/Daughter relationship between Hilde and Erika that persists throughout the story is slightly complex. The first point of tension between the women is simply their differences in generation. Erika comes from an educated generation that is encouraged to ask questions and find truth, while Hilde was taught to never question authority or rules. Erika is taught to be active and bold, yet Hilde was taught to be passive and delicate. There is much misunderstanding due to age and history differences. Also, Hilde is extremely envious of Erika's education and opportunites. This also causes a rift between mother and daughter. Hilde dislikes the fact that Erika has used her education to become a mere writer.[12]

Erika is very demanding towards Hilde in wanting answers; Hilde is her daughter's only tie to personal history. Erika can not discover her heritage without the aid of her mother, yet her mother wants to forget her painful past and move on to a better future. Erika seems fascinated with the past while Hilde is engrossed with the future. Strain is common in cyclical relationship patterns such as this one.[13]

Use of the Word 'Shadows'[edit]

The persistent use of the word shadow stems from the original Austrian text. In Austrian the word refers to a specific type of shadow that is only cast in February due to the position of the earth and the sun during that specific time of the year. The shadows of February are more defined; as was the evil of the villagers on February 2, 1945. Hilde often uses shadows in reference to shameful or painful events, people, and memories. Shadows seem to be fitting to the nature of novel since Hilde is always attempting to escape the shadowy pain of her past.[14]

Style[edit]

Literary Techniques[edit]

February Shadows contains several nontraditional literary devices that became popular in Austrian literature in the 1980's in novels that dealt with extreme or war-related subject matter. Reichart utilizes these unconventional devices to illustrate Hilde's denial of pain and her struggle to remain emotionally stable. The use of fragmented sentences allows the reader to understand Hilde's inability and refusal to connect one idea to another as she attempts to repress memories. The truncated thoughts represented by the short and incomplete sentences display her own prohibition to remember the past. Even the use of incorrect punctuation enhances the emotions of the story. Reichart often places periods in the middle of sentences creating sharp endings to ideas as if Hilde is smothering her own thoughts. She also ends questions without questions marks as if Hilde is hopelessly inquiring and does not expect to receive an answer.[15]

The plot follows a nonsequential structure; it switches from past memories to present experiences often entangling the two. This meshing of memories and experiences creates a sense of confusion between past and present in which no details are exceptionally concrete. Reichart also uses excessive repetition of words and phraseology throughout the entire book to highlight themes and recurring ideas. The redundancy generates feelings of urgency and obsession throughout the plot. Coupled with repetition is the profuse use of emphasis on certain recurring words such as alone, exclusion, and guilt. The text is scattered with these words in all capital letters to symbolize their importance to the main points and the extreme feelings Hilde posesses about them.[16]

Often throughout the novel Hilde will not refer to herself as "I," she refers to herself in third person or merely speaks without using a noun or pronoun. This relates to her self-loathing and her unwillingness to see herself honestly for fear of who she really is. Similarly to the disuse of the pronoun "I" Hilde also does not allow herself to use the word "my" in reference to her parents, husband, and daughter. She inserts an impersonal "the" in its place. For example she does not say "my" mother, but "the" mother. In the original Austrian text the use of the impersonal article was meant to show estrangement between Hilde and her family, and Reichart asked that the English translation retain the article even though it did not translate directly.[17]

The overall effect of the literary techniques used by Reichart indicate Hilde's retrainment of painful memories, her obsession with guilt and self-loathing, her inability to resolve anxiety, and the inadequacy of words to capture her feelings. With these devices Reichart attempts to allow the reader to see inside the mind of an extremely disturbed Hilde.[18]

Elements of the Psychological Novel[edit]

Three major elements of the writing style indicate that the book can be classified as a psychological novel. The first is the emphasis of the mind and inner thoughts rather than the plot line and movement of the story. The feelings behind all actions chosen are far more important than the actions themselves; the actions are mere secondary behaviors in response to the psychological decisions of the character. Another element of the psychological novel that is exemplified in the book is the stream of consciousness, or inner monologue style of writing. The majority of the storyline takes place internally in the mind of the lead character rather than externally through actions and interactions with other characters. In addition to inner monologues memories of dialogues or even imagined dialogues with other important characters aid in the plot movement. The final element of the psychological novel displayed in February Shadows is the use of a non-chronological timeline and excessive flashbacks. The effect allows the reader to follow the character thought by thought through memories, feelings, and contemplations; thus creating the illusion that the reader is inside the mind of the character rather than observing as a third party such as in classical novels.[19]

[[:File:T Bernhard.jpg|right|thumb|Thomas Bernhard was a contemporary of Reichart's who also employed the use of key themes and phrases to represent strong emotions.]]

Similar Authors[edit]

Reichart utilizes techniques in her novel that are similar to other Austrian authors from both the early 20th century and the early 1980's.[20] Similar to Franz Kafka Reichart employs alternating run-on and fragmented sentences to display the emotions of her character, and also creates an poignant plot by using ambiguous words which could potentially posess multiple meanings in the text.[21] Like Ödön von Horváth Reichart has the ability to unroot and publicly display difficult events through dramatacized means. In the novels authored by Peter Handke the use of extreme psychological activity to drives the plot, congruently to Reichart's novel;[22] and her use of key themes and phrases which represent the innate emotional processes can also be seen in the writings ofThomas Bernhard.[23]

Background[edit]

The Rabbit Hunt of the Mill District[edit]

Mühlviertler Hasenjagd also known as "The Rabbit Hunt of the Mill District" took place on February 2, 1945. An estimated 500 prisoners escaped from special barracks number 20 of the Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp. The prisoners held in these barracks were considered to be intellectual Soviet Officers who were being held for fear of revolt against the National Socialism of Germany. When the alarm in nearby Mühlviertler sounded all citizens, despite age or gender, were instructed by members of the Austrian National Socialist Party (who were under the jurisdiction of the Nazi Party) to hunt down the escaped prisoners. There was a large massacre in which nearly all of the prisoners were captured and murdered by either Nazi officers or the civilians themselves. There were only seventeen known survivors.[24]

About the Author[edit]

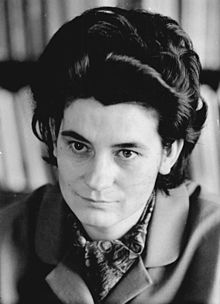

Elisabeth Reichart was born in Muhlviertel, Austria, but never learned of the event of Mühlviertler Hasenjagd until her grandmother conveyed it to her as an adult. Her shock at the hidden and unspoken tragedy initially compelled her to begin research about the event. During this time the Austrian government developed renewed interest in Austria's role during World War II and Reichart began to unearth documentation regarding the resistance movement against the Nazi Party as it became available for the first time. Reichart wrote her dissertation about the resistance movement and the silence of Austria during World War II. Soon after she began the writing of her first novel, February Shadows. [25] Reichart has developed into a well-known Austrian writer since the release of February Shadows. and has since produced five novels, a book of short stories, several dramas, and a collection of radio plays. In 1993 she received the Austrian National Prize for the Promotion of Literature and in 1995 she was given the prestigious Elias Canetti Grant.[26]

Reichart's Literary Works[edit]

- Februar Schatten 1984 (February Shadows)

- Komm über den See 1988 (Come Across the Lake)

- La Valse 1992

- Fotze 1993

- Nachtmär 1995 (Nighttale)

- Das vergessene Lächeln der Amaterasu 1990 (The Forgotten Smile of the Amaterasu) [27]

About the Afterword[edit]

The afterword of the novel was written by Christa Wolf, a famous German literary critic and writer.[28] Wolf gives a brief background of Reichart's discovery of Mühlviertler Hasenjagd and also her interpretation of the story. She praises two main themes: the struggle of silence, and the liberation of the female voice through psychological writing. Wolf also notifies the reader of consistent symbolism of throughout the book and its application to reality.[29]

Wolf's Literary Works[edit]

- Der geteilte Himmel 1963 (''Divided Heaven'').

- Nachdenken über Christa T. 1968 (''The Quest for Christa T.'')

- Kindheitsmuster 1976 (Patterns of Childhood)

- Kein Ort. Nirgends 1979

- Kassandra 1983 (''Cassandra'')

- Was bleibt 1990 (What Remains)

- Medea 1996

- On the Way to Taboo 1994

- Auf dem Weg nach Tabou 1995 (translated as Parting from Phantoms)

- Leibhaftig 2002 [30]

Publication History[edit]

Februar Schatten was originally written in the German language and was first printed by Verlag der Osterreichischen Staatsdruckerei in Vienna in 1984. It was reissued by Aufbau Verlag in Berlin by 1985 and the afterword by Christa Wolf was added. February Shadows was translated to English in 1989 by Donna L. Hoffmeister who also added a commentary at the end of the book in order to aid English speakers who would not completely understand either the language or the context. Ariadne Press in Riverside, California published the English version and Georg Eisler designed the cover art.[31]

Reception[edit]

The novel was received remarkably well by the younger generation in the 1980's. The book represented to them a story of truth that was hidden for a very long time. In a time where Austria was starting to take on responsibility for its nonaction during World War II February Shadows pointed out the exact problems of the past. Reichart displayed to her own nation that ignoring and forgetting events such as Mühlviertler Hasenjagd was unacceptable and needed to be recognized. The older generation who had lived through the war felt that February Shadows was controversial and inappropraite. Much like the character Hilde in the story they felt as if the past should stay in the past and that there was a reason for Austrian silence during World War II; protection of lives.[32] Another major theme that was received greatly by the academic public was the literal liberation of the young female voice during Mühlviertler Hasenjagd and consequently during the war. Reichart allowed all readers to see into the mind of a tormented, silenced girl and her voice became free. Through Reichart's book the Austrian readers felt as if they were making a positive progressive movement in history by becoming aware of the tragedy of the war, and accepting their place and major faults in it.[33]

Sources[edit]

Citations and Notes[edit]

- ^ Reichart, pg 1-141.

- ^ Reichart, pg 1-141.

- ^ Wolf, pg 143.

- ^ Reichart, pg 128.

- ^ Michaels, pg 17.

- ^ Hoffmeister, pg 151.

- ^ "Elisabeth Reichart-The Art of Confronting Taboos."

- ^ Reichart, pg 66.

- ^ "Elisabeth Reichart-The Art of Confronting Taboos."

- ^ Hoffmeister, pg 149.

- ^ Reichart, pg 28.

- ^ Michaels, pg 16-17.

- ^ Hoffmeister, pg 153.

- ^ Hoffmeister, pg 160.

- ^ Hoffmeister, pg 156.

- ^ Hoffmeister, pg 156.

- ^ Hoffmeister, pg 148.

- ^ DeMeritt.

- ^ "Psychological Novel"

- ^ Hoffmeister pg 156.

- ^ Hornek.

- ^ "Peter Handke."

- ^ "Thomas Bernhard."

- ^ Reichart pg 142.

- ^ Michael's pg 11, Wolf pg 144.

- ^ DeMeritt

- ^ DeMeritt

- ^ "Christa Wolf."

- ^ Wolf, pg 143-145.

- ^ "Christa Wolf."

- ^ Reichart, pg 1-162.

- ^ Demeritt and Michaels pg 11.

- ^ Hoffmeister pg 147-162.

Bibligraphy[edit]

- "Christa Wolf." FemBio. April 19, 2010. <http://www.fembio.org/english/biography.php/woman/biography/christa-wolf/>

- DeMeritt, Linda. “The Art of Confronting Taboos.” Department of Modern and Classical Languages of Allegheny College. 2000. <http://webpub.allegheny.edu/employee/l/ldemerit/reichtrans.html>

- “Elisabeth Reichart- February Shadows.” Studies in Austrian Literature, Culture, and Thought. Ariadne Press. 2004.

- Hoffmeister, Donna L. “Commentary.” February Shadows. Riverside: Ariadne Press, 1989.

- Hornek, Daniel. "Franz Kafka Biography." Franz Kafka Website. 1999. <http://www.kafka-franz.com/kafka-Biography.htm>

- Killough, Mary Klein. “Freud’s Vienna, Then and Now: The Problem of Austrian Identity.” Blue Ridge Torch Club. 2006. <http://www.patrickkillough.com/international-un/vienna.html>

- Michaels, Jennifer E. “Breaking the Silence: Elisabeth Reichart's Protest against the Denial of the Nazi past in Austria.” German Studies Review. Vol. 19, No. 1 (1996): pp. 9–27. JSTOR. German Studies Association. March 31, 2010.

- "Odon von Horvath." Moonstruck Drama. 19 April 2010.

- "Peter Handke." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2010. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 19 Apr. 2010 <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/254210/Peter-Handke>.

- "Psychological Novel." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2010. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 19 Apr. 2010 <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/481652/psychological-novel>.

- Reichart, Elisabeth. February Shadows. Riverside: Ariadne Press, 1989.

- "Thomas Bernhard." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2010. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 19 Apr. 2010 <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/62516/Thomas-Bernhard>.

- Thornton, Dan Franklin. “Dualities: Myth and the unreconciled past in Austrian and Dutch literature of the 1980s.” Ph.D. dissertation, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, United States -- North Carolina. Proquest. Publication No. AAT 9968684. March 31, 2010.

- Wolf, Christa. “Afterword.” February Shadows. Riverside: Ariadne Press, 1989.