User:Dudley Miles/sandbox

Brochfael ap Meurig[a] (fl. 880s-910s[6]) was joint king of Gwent in south-east Wales, together with his brother Ffernfael ap Meurig.

Family[edit]

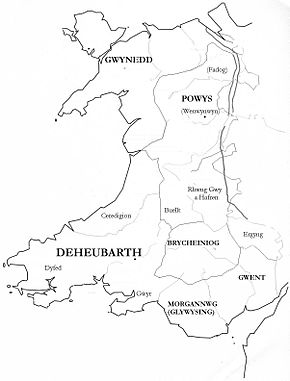

Brochfael and his brother Ffernfael ap Meurig were sons of Meurig ab Arthfael,[b] who died in 874. The genealogist Peter Bartrum described Meurig as king of king of Gwent (later Monmouthshire) and Glywysing (later Glamorgan)[8] but Patrick Sims-Williams states that there is no evidence that he and his sons had any power outside Gwent.[9]

Background[edit]

In 878, King Alfred the Great of Wessex defeated the Vikings at the Battle of Edington and around the same time King Ceolwulf of Mercia defeated and killed Rhodri Mawr, the powerful king of the north Welsh Kingdom of Gwynedd. Rhodri's sons soon recovered their father's power and in the early 880s the dominant powers in Wales were Gwynedd over the south-west Welsh kingdom of Dyfed and Ceolwulf's successor as ruler of Mercia, Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians, over Gwent and Glywysing in the south-east. In 881, the sons of Rhodri defeated Æthelred at the Battle of the Conwy, a victory which was described in Welsh annals as "revenge by God for Rhodri".[10]

Kingship[edit]

The historian Wendy Davies dates Brochfael's rule over Gwent from about 872 to around 910, and his father's rule from c.850 to c. 870.[11] Meurig ruled a large area of south-east Wales, encompassing Gwent and Glywysin, whereas Brochfael only ruled Gwent.[12] Thomas Charles-Edwards says that in the 880s, Brochfael and Ffernfael ruled Gwent while their first cousin Hywel ap Rhys ruled Glywysin.[13] The kingship of Glywysin seems to have been superior, and Hywel was probably an over-king allowing his cousins to rule Gwent.[14]

In early medieval Wales, it was common for brothers to share the kingship.[15] There are several charters in the Book of Llandaff which show Brochfael as a witness, but only two with his father for Ffernfael, who may have been subordinate to Brochfael.[16]

In about 868, King Meurig surrendered the church at Tryleg and returned it to Bishop Cerennyr in the presence of his sons Brochfael and Ffernfael.[17]

Brochfael and his brother both witnessed charters without royal status in the times of Bishops Nudd and Cerenhir, and Brochfael witnessed charters as king in the times of bishops Cerenhir and Cyfeilliog.[2] In about 905, there was a disagreement between Brochfael's familia (household) and Cyfeilliog's. Cyfeilliog was awarded an "insult price" "in puro auro" (in pure gold) of the worth of his face, lengthwise and breadthwise. Brochfael was unable to pay in gold and paid with six modii (about 240 acres (97 ha) of land at Llanfihangel instead.[18] Around five years later, there was a dispute between Cyfeilliog and Brochfael about a church in Monmouth and its territory, and judgement was again given in Cyfeilliog's favour.[19] Most of the grants to Cyfeilliog are from Brochfael.[20]

Like other Welsh kings, Brochfael had large landed estates, and he made several grants of land on the coast of the Severn Estuary.[21] In two Llandaf charters, he granted fishing rights in estates west of Sudbrook Point.[22] He was excommunicated by a synod as a result of a dispute with Bishop Cyfeilliog.[3]

Grants to Cyfeilliog between the 890s and 920s were all of land in Gwent, and Brochfael was the main grantor.[23]

Æthelred's defeat at the Conwy ended his attempt to maintain Mercian domination of north Wales, but he still tried to maintain his rule over Gwent and Glywsysing. Alfred became the competitor of Mercia for their allegiance and Æthelred's violence towards the south-eatern Welsh kingdoms drove their rulers to submit to Alfred and seek his protection. Æthelred himself soon followed in abandoning the attempt to maintain his independence and submitting to the West Saxon king. In the view of the historian of Wales Thomas Charles-Edwards, the Welsh kings' decision may have been a significant factor in Æthelred's decision, and thus in an important step towards the unity of England.[24]

In his Life of King Alfred, the Welsh monk Asser listed Brochfael among Welsh kings who submitted to King Alfred. He wrote:

- At that time [around 887], and for a considerable time before then, all the districts of right-hand [southern] Wales belonged to King Alfred, and still do.The is to say, Hyfaidd, with all the inhabitants of the kingdom of Dyfed, driven by the might of the six sons of Rhoddri [Mawr], had submitted himself to King Alfred's royal overlordship. Likewise, Hywel ap Rhys (the king of Glywysing) and Brochfael and Ffernfael (sons of Meurig and kings of Gwent), driven by the might and tyrannical behaviour of Ealdorman Æthelred and the Mercians, petitioned King Alfred of their own accord, in order to obtain lordship and protection from him in the face of their enemies.[25]

The Book of Llandaff agrees with Asser in describing Hywel ap Rhys as king of Glywysing, but it records many grants by him in Gwent than Glamorgan.[26]

Legacy[edit]

In the view of the historian Peter Bartrum, Brochfael was probably succeeeded as king of Gwent by Arthfael ap Hywel, the son of King Hywel ap Rhys.[2] Arthfael is shown as king in a charter dating to about 890.[11] The royal line descended from Meurig ended with Brochfael, but he may have been the father of Gwriad ap Brochfael.[27] Patrick Sims-Williams says that Hywel's son Owain ap Hywel may have ruled Gwent and Glywysing from around 893,[28] while Charles-Edwards thinks that both kingdoms were probably ruled by Owain by 918.[29] Manuscript D of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle states that in 927 Owain, king of the people of Gwent, was one of the British rulers who submitted to Æthelstan.[30]

Note[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Guy 2020, p. 61; Charles-Edwards 2013, p. 253.

- ^ a b c Bartrum 1993, p. 60.

- ^ a b Haddan & Stubbs 1869, p. 207 n..

- ^ Sims-Williams 2019, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Evans & Rhys 1893, p. 234.

- ^ Davies 1978, pp. 19, 60.

- ^ Moore 1990, p. 13.

- ^ Bartrum 1993, p. 477.

- ^ Sims-Williams 2019, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2013, pp. 489–491.

- ^ a b Davies 1978, p. 70.

- ^ Davies 1978, pp. 82, 95.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2013, p. 505.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2011, pp. 76–78.

- ^ Davies 1978, p. 102.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2011, p. 76; Sims-Williams 2019, p. 122.

- ^ Davies 1978, p. 177.

- ^ Evans & Rhys 1893, pp. 233–234; Davies 1979, pp. 123; Davies 1978, pp. 60, 183.

- ^ Davies 1978, p. 182.

- ^ Sims-Williams 2019, p. 172.

- ^ Davies 1978, p. 98.

- ^ Edwards 2023, p. 210.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2004.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2013, pp. 490–492.

- ^ Keynes & Lapidge 1983, pp. 27, 93–94, 96.

- ^ Sims-Williams 2019, p. 121.

- ^ Davies 1978, p. 95; Bartrum 1993, p. 60.

- ^ Sims-Williams 2019, p. 117.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2013, pp. 495, 505.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2013, p. 511; Whitelock 1979, p. 218.

Bibliography[edit]

- Bartrum, Peter (1993). A Welsh Classical Dictionary: People in History and Legend up to about A. D 1000. Aberystwyth, UK: The National Library of Wales. ISBN 978-0-907158-73-8.

- Charles-Edwards, Thomas (2004). "Cyfeilliog (d. 927)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5420. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Charles-Edwards, Thomas (2011). "Dynastic Succession in Early Medieval Wales". In Griffiths, R. A.; Schofield, P. R. (eds.). Wales and the Welsh in the Middle Ages. Cardiff, UK: University of Wales Press. pp. 70–88. ISBN 978-0-7083-2446-2.

- Charles-Edwards, Thomas (2013). Wales and the Britons 350–1064. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821731-2.

- Davies, Wendy (1978). An Early Welsh Microcosm. London, UK: Royal Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-901050-33-5.

- Davies, Wendy (1979). The Llandaff Charters. Aberystwyth, UK: National Library of Wales. ISBN 978-0-901833-88-4.

- Edwards, Nancy (2023). Life in Early Medieval Wales. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-873321-8.

- Evans, John Gwenoguryn; Rhys, John, eds. (1893). The Text of the Book of Llan Dâv. Oxford, UK: J. Gwenoguryn Evans. OCLC 632938065.

- Guy, Ben (2020). Medieval Welsh Genealogies. Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-78327-513-7.

- Haddan, Arthur; Stubbs, William, eds. (1869). Councils and Ecclesiastical Documents Relating to Great Britain and Ireland. Vol. I. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. OCLC 1046288968.

- Keynes, Simon; Lapidge, Michael, eds. (1983). Alfred the Great: Asser's Life of King Alfred & Other Contemporary Sources. London, UK: Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-14-044409-4.

- Moore, Donald (April 1990). "The Indexing of Welsh Person Names". The Indexer. 17 (1): 12–20. ISSN 0019-4131.

- Sims-Williams, Patrick (2019). The Book of Llandaff as a Historical Source. Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-78327-418-5.

- Whitelock, Dorothy, ed. (1979). English Historical Documents, Volume 1, c. 500–1042 (2nd ed.). London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-14366-0.