Historic Centre of Lima

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

The Cathedral of Lima located in the main square of the historic center | |

| Location | Lima, Peru |

| Criteria | Cultural: (iv) |

| Reference | 500bis |

| Inscription | 1988 (12th Session) |

| Extensions | 1991, 2023 |

| Area | 259.36 ha (640.9 acres) |

| Buffer zone | 766.7 ha (1,895 acres) |

| Coordinates | 12°3′5″S 77°2′35″W / 12.05139°S 77.04306°W |

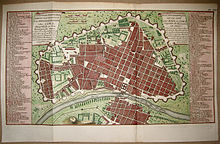

The Historic Centre of Lima (Spanish: Centro histórico de Lima) is the historic city centre of the city of Lima, the capital of Peru. Located in the city's districts of Lima and Rímac, both in the Rímac Valley, it consists of two areas: the first is the Monumental Zone established by the Peruvian government in 1972,[1] and the second one—contained within the first one—is the World Heritage Site established by UNESCO in 1988,[2] whose buildings are marked with the organisation's black-and-white shield.[a]

Founded on January 18, 1535, by Conquistador Francisco Pizarro, the city served as the political, administrative, religious and economic capital of the Viceroyalty of Peru, as well as the most important city of Spanish South America.[4] The evangelisation process at the end of the 16th century allowed the arrival of several religious orders and the construction of churches and convents. The University of San Marcos, the so-called "Dean University of the Americas", was founded on May 12, 1551, and began its functions on January 2, 1553 in the Convent of Santo Domingo.[5]

Originally contained by the now-demolished city walls that surrounded it, the Cercado de Lima features numerous architectural monuments that have survived the serious damage caused by a number of different earthquakes over the centuries, such as the Convent of San Francisco, the largest of its kind in this part of the world.[2][6] Many buildings of the are joint creations of artisans, local artists, architects and master builders from the Old Continent.[2] It is among the most important tourist destinations in Peru.

History[edit]

The city of Lima, the capital of Peru, was founded by Francisco Pizarro on 18 January 1535 and given the name City of the Kings.[7] Nevertheless, with time its original name persisted, which may come from one of two sources: Either the Aymara language lima-limaq (meaning "yellow flower"), or the Spanish pronunciation of the Quechuan word rimaq (meaning "talker", and actually written and pronounced limaq in the nearby Quechua I languages). It is worth nothing that the same Quechuan word is also the source of the name given to the river that feeds the city, the Rímac River (pronounced as in the politically dominant Quechua II languages, with an "r" instead of an "l"). Early maps of Peru show the two names displayed jointly.

Under the Viceroyalty of Peru, the authority of the viceroy as a representative of the Spanish monarchy was particularly important, since its appointment supposed an important ascent and the successful culmination of a race in the colonial administration. The entrances to Lima of the new viceroys were specially lavish. For the occasion, the streets were paved with silver bars from the gates of the city to the Palace of the Viceroy.[citation needed]

In 1988, UNESCO declared the historic centre of Lima a World Heritage Site for its originality and high concentration of historic monuments constructed during the viceregal era.[2] In 2023, it was expanded with two exclaves to include the Quinta and Molino de Presa and the Ancient Reduction of Santiago Apostle of Cercado.[2]

On January 18, 2024, the city's 489th anniversary, president Dina Boluarte announced a "special regime" that targets the area in order to allow restoration and repair works to take place.[8]

List of sites[edit]

The World Heritage Site, divided into three zones,[2] features a number of landmarks.

Historic Centre of Lima[edit]

The main zone is that of the Historic Centre of Lima (266.17 ha; buffer zone: 806.71 ha),[2] which features the following:

| Name | Location | Notes | Photo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Balconies of Lima | Various | Over 1,600[citation needed] were built in total in both the viceregal and republican eras of the city. They have been crucial in UNESCO's declaration of the historic centre as a World Heritage Site.[2] |  |

| Acho Bullring | Jr. Marañón 569 Jr. Hualgayoc 332 |

It is the oldest bullring in the Americas and the second-oldest in the world after La Maestranza, in Spain. It opened on January 30, 1766, and has a seating capacity of 13,700 people. |  |

| Archbishop's Palace | Jr. Junín & Carabaya | The home of the Archbishop of Lima, it was turned into an episcopal seat in 1541 by Pope Paul III and rebuilt in 1924 by architects Claude Sahut and Ricardo de Jaxa Malachowski as part of the city works commissioned by Augusto B. Leguía in preparation of the centennial celebrations of the Battle of Ayacucho.[9] |  |

| Basilica and Convent of Saint Augustine | Jr. Camaná & Ica | Located in front of a public square of the same name, it has been run by the Augustinian friars since its foundation, and belongs to the Province of Our Lady of Grace of Peru. |  |

| Basilica and Convent of Saint Dominic | Jr. Camaná & Conde de Superunda | The 16th century complex, originally named after Our Lady of the Rosary, is named after Saint Dominic. It is also the site where the Royal University of Lima was founded in 1551, and was elevated to basilica in 1930. |  |

| Basilica and Convent of Saint Francis | Jr. Áncash & Lampa | The 17th century complex is named after Francis of Assisi. It is the site of the Museum of Religious Art and of the Zurbarán Room, as well as an underground network of galleries and catacombs that served as a cemetery during the Viceregal era. |  |

| Basilica and Convent of Saint Peter | Jr. Azángaro & Ucayali | The 17th century complex, formerly named after Saint Paul and featuring a college of the same name, is named after Saint Peter since 1767. It is the burial site of Viceroy Ambrosio O'Higgins, as well as the site of the heart of the Viceroy Count of Lemos.[10] |  |

| Basilica and Convent of Our Lady of Mercy | Jr. Unión & Sta. Rosa | The 16th century complex is named after Our Lady of Mercy, who serves as the patroness of the Peruvian Armed Forces. Its Churrigueresque style dates back to the 18th century. The public square next to it was the location of one of José de San Martín's proclamations of the independence of Peru in 1821.[11] |  |

| Casa de Aliaga | Jr. Unión 225 | The building—the oldest in the city—dates back to May 1536, belonging to Conquistador Jerónimo de Aliaga and built on top of a pre-Columbian sanctuary. It was destroyed by the earthquake of 1746 and rebuilt by Juan José Aliaga y Sotomayor. In the 19th century a series of works were carried out.[12] |  |

| Casa Arenas Loayza | Jr. Junín 270 | Unlike many other similar residences from the mid-19th century, its plan does not develop around a central patio or in general around any axis. Its interior is decorated with plasterwork with a floral motif. The ground floor is mostly intended for longitudinal shops. |  |

| Casa de Correos y Telégrafos | Jr. Conde de Superunda 170 | Originally the city's post office since 1872, it now hosts two museums: one dedicated to philately, inaugurated in 1931, and another one dedicated to Peruvian cuisine, opened in 2011. |  |

| Casa de Divorciadas | Jr. Carabaya 641 | Built in the 18th century, it originally functioned as a residence for divorced women.[13] It is currently operated by de Charity of Lima.[14] |  |

| Casa Fernandini | Jr. Ica 400 | The building was designed by Claude Sahut in an eclectic style for the miner Eulogio Fernandini and his family. It is currently a museum where cultural activities take place regularly. |  |

| Casa de Goyeneche | Jr. Ucayali 358 | The 959.20 m2 two-storey building was built during the 18th century and is named after the family that formerly owned it. After passing through a series of different owners, it was ultimately acquired by the Banco de Crédito del Perú in 1971.[15] |  |

| Casa de la Literatura Peruana | Jr. Áncash & Carabaya | Originally a train station named after the adjacent church, the building has since been converted into a cultural centre that was inaugurated on October 20, 2009. |  |

| Casa Marcionelli | Jr. Carabaya 955 | Built by Swiss businessman Severino Marcionelli, it housed his offices, a consulate of Switzerland, and was eventually burned down in 2023, with only the first floor's façade remaining.[16][17] |  |

| Casa de Moneda | Jr. Junín 781 | The building's houses the national mint of the country, whose origin dates back to 1565. |  |

| Casa del Oidor | Jr. Junín & Carabaya | The building was built on two of the four plots that made up one of the 117 blocks into which Lima was initially divided. Also damaged and rebuilt after the 1746 earthquake,[18] it is best known for the large balcony that runs through its façade.[19] |  |

| Casa O'Higgins | Jr. Unión 554 | Named after Bernardo O'Higgins, who lived and died there, it is currently operated by the Riva-Agüero Institute. |  |

| Casa de Osambela | Jr. Conde de Superunda 298 | Built on the former grounds of a novitiate of the Dominican Order that was destroyed during the 1746 earthquake, it is currently the headquarters of the Academia Peruana de la Lengua and the regional office of the Organization of Ibero-American States. |  |

| Casa de Pilatos | Jr. Áncash 390 | Built in the late 16th century, it was occupied by various families of the aristocracy of Lima for most of its history,[20][21] being purchased by the government during the 20th century. It currently functions as the de facto headquarters of the Constitutional Court. |  |

| Casa Riva-Agüero | Jr. Camaná 459 | This house was constructed in the 18th century by the Riva Agüero family, whose last member, the intellectual José de la Riva-Agüero, donated it to the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru. It currently serves as the headquarters of the university's Riva-Agüero Institute, where its archive and library are located. |  |

| Catacombs of Lima | Basilica and Convent of St. Francis | The extensive underground network was built c. 1600[22] and functioned as a cemetery until 1810,[23] with some 25,000 bodies lying within.[24] It was reopened in 1950,[23] currently working as a museum. |  |

| Church of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph | Jr. Camaná & Moquegua | Built in 1678,[25] it functioned as a shelter for orphaned and abandoned youth owned by a couple, eventually becoming a religious complex through donations. |  |

| Church of Saint Camillus | Jr. Áncash & Paruro | Named after the order based there, it was rebuilt after the 1746 earthquake and currently houses a health centre. Inside of the church is a statue by Juan Martínez Montañés.[26] |  |

| Church of the Sacred Heart | Jr. Azángaro 776 | Rebuilt after the 1746 earthquake, it was inaugurated on April 6, 1766. It is the only Catholic temple in Peru and Latin America with an elliptical plan, similar to those of Austria, and is designed in the Rococo limeño style. |  |

| Church of Saint Lazarus | Av. Francisco Pizarro & Jr. Trujillo | Built in 1586, it was the first church built in the area. Since then it has been rebuilt several times after being damaged due to the many earthquakes the city has experienced. Up until the 19th century, the church gave the neighbourhood of San Lázaro its name, until it separated from Lima District as Rímac District.[27] |  |

| Church of Saint Liberata | Jr. 22 De Agosto 100 | The church was first built in 1716, with the Cruciferous Fathers of Good Death taking charge of its administration from 1745 to 1826. Its name comes from the patron saint of Sigüenza, the hometown of then Viceroy Diego Ladrón de Guevara. |  |

| Church of Saint Sebastian | Jr. Chancay & Ica | It is the third parish to be built in Lima, founded in 1554. Its altarpiece dates back to the 18th century, and its fountain dates back to 1888. |  |

| Church of the Trinitarians | Jr. Áncash 790 | The land was originally occupied by the Beaterio de las Trinitarias, which became a convent. The church originated as part of that monastery and was completed in 1722. |  |

| Church of Our Lady of Copacabana | Jr. Chiclayo 400 | Rebuilt after the 1746 earthquake with funds from its resident brotherhood and from local devotees, it is shaped like a Latin cross, with short arms and a dressing room behind the front wall. |  |

| Church of Our Lady of Mount Carmel | Jr. Junín & Huánuco | The church was originally established as a retreat for poor girls at the beginning of the 17th century, becoming a monastery in 1625. The restoration works that followed the earthquakes 1687 and 1940 made major changes in its floor plan. |  |

| Church of Our Lady of Patronage | Jr. Manco Cápac 164 | The beguinage and the first chapel were completed in 1688, while the temple as a whole was only completed in 1754. In 1919, the beguinage was transformed into the convent of the Dominican nuns of the Most Holy Rosary. |  |

| Church of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary | Av. Garcilaso de la Vega 1131 | Built in 1606, it had to be restored after the earthquakes of 1687 and 1746, and a fire in 1868.[28] A statue donated by the city's French colony was placed in the public square in front of the church as part of the centennial celebrations of 1921. |  |

| Club Nacional | Plaza San Martín | Founded on October 19, 1855, it has been the meeting place for the Peruvian aristocracy throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, as its members are members of the most distinguished and wealthy families in the country. |  |

| Club de la Unión | Jr. Unión 364 | Founded on October 10, 1868, it is headquartered at the palace of the same name, itself inaugurated in 1942. Its founders include notable historical figures of the history of Peru, many of which served during the War of the Pacific. |  |

| Convent of Our Lady of the Angels | Alameda de los Descalzos | The convent was founded in 1595 by the Franciscan Order and under the auspices of Archbishop Toribio de Mogrovejo. In 1981, a museum was opened in its premises. |  |

| Edificio Fernando Belaúnde Terry | Jr. Huallaga 364 | The building houses the Library of Congress of Peru in its basement. | — |

| Edificio Giacoletti | Plaza San Martín | The building dates back to 1912, and originally featured Art Nouveau features on its façade, which were removed in the 1940s. A fire burnt down most of the building in 2018.[29] |  |

| Edificio Javier Alzamora Valdez | Av. Abancay & Colmena | Formerly the headquarters of the Ministry of Education, it's the main location of the Superior Court of Justice of Lima, part of the Judiciary of Peru.[30] |  |

| Government Palace | Jr. Junín | Originally built to be the residence of Francisco Pizarro, it was rebuilt under the presidency of Oscar R. Benavides by architects Claude Sahut and Ricardo de Jaxa Malachowski, with construction works finishing in 1937. The palace currently serves as the residence of the President of the Republic, and features a memorial obelisk at its entrance. |  |

| Gran Hotel Bolívar | Plaza San Martín | Part of a program to modernise Lima, the hotel was constructed on what was state property. The hotel was inaugurated on December 6, 1924, as part of the centennial celebrations commemorating the Battle of Ayacucho. |  |

| Hotel Comercio | Jr. Áncash & Carabaya | The hotel, located next to Government Palace, is bestknown for a murder that took place on June 24, 1930,[31] and for the Bar Cordano, located on its first floor and visited by almost every president since its inception.[32] |  |

| Hotel Maury | Jr. Carabaya & Ucayali | A three-star hotel, it is considered one of the oldest hotels in both Peru and the Pacific coast, having been founded in 1835. It was rebuilt in 1945, giving the building its current modernist appearance. |  |

| Legislative Palace | Plaza Bolívar | Built during the presidency of Óscar R. Benavides on the site of one of the buildings once occupied by the University of San Marcos, it started hosting the Congress of Peru in 1938. |  |

| Lima Stock Exchange Building | Jr. Carabaya & Sta. Rosa | The building, inaugurated in 1950, housed the Lima Stock Exchange from 1997 to 2022 until its acquisition by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which has since repurposed the building. |  |

| Maternidad de Lima | Jr. Sta. Rosa 941 | The maternity hospital was established through a supreme decree on October 10, 1826, moving to its current location in 1934 after a series of location changes. |  |

| Metropolitan Cathedral | Jr. Carabaya & Huallaga | Built alongside the city in 1535, its current form was built between 1602 and 1797, and is dedicated to John the Apostle. Its interior features a gold-plated altar, as well as the tomb of Francisco Pizarro. A Te Deum mass is traditionally held annually as part of the national day celebrations. Another custom restarted by Cardinal Juan Luis Cipriani, is to celebrate mass every Sunday at 11:00 a.m. In 2005, Mayor Luis Castañeda oversaw a project of illuminating the exterior of the cathedral with new lights. |  |

| Monastery of Saint Clare | Jr. Jauja 449 | The first building is from 1606, but the current temple is from the 19th century, occupying a large part of the extensive block in which it is located. A former mill of the same name is located across the street from the monastery. |  |

| Monastery of Saint Rose of Lima | Jr. Ayacucho & Sta. Rosa | Built in the 17th and 18th centuries, it consists of the church and monastery next to the house in which Saint Rose of Lima lived and spent the last three months of her life until her death in her room on August 24, 1617. Said room has since been converted into a chapel.[33] |  |

| Municipal Palace | Jr. Unión | Built in 1939, the building serves as the city hall, housing the Metropolitan Municipality of Lima. |  |

| Museum of Congress and the Inquisition | Jr. Junín 548 | Located in the neighbourhood of Barrios Altos, the building served as the former headquarters of the Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition and later as the seat of the Peruvian Senate until 1939. The museum dedicated to both occupants was opened on July 26, 1968. |  |

| Museum of Italian Art | P.° de la República 250 | The only European arts museum of Peru, it was the gift from the Italian colony to the city as part of the centennial celebrations that took place in 1921. Designed by architect Gaetano Moretti, it was inaugurated on November 11 of the same year. |  |

| National Library of Peru | Av. Abancay | Founded by José de San Martín in 1821, it was looted during the military occupation of the city during the War of the Pacific and was almost completely destroyed in a fire on May 10, 1943. It has since been restored and is open to the public. |  |

| Old San Bartolomé Hospital | Jr. Sta. Rosa | The former premises of San Bartolomé Hospital were in use from its foundation in 1651 until 1988, when it was moved to its current site in Alfonso Ugarte Avenue. |  |

| Plaza Bolívar | Formerly known as the site of the Tribunal of the Inquisition, it has been extensively modified throughout its history and currently houses an equestrian statue of Simón Bolívar and a tomb to an unknown soldier. |  | |

| Plaza Mayor | The site of the foundation of the city, it also served as the location of one of José de San Martín's proclamations of the independence of Peru in 1821.[11] |  | |

| Plaza San Martín | The square was built to coincide with the centennial celebrations that took place in 1921, having replaced a train station and featuring an equestrial monument to José de San Martín, the work of Spanish sculptor Mariano Benlliure. |  | |

| Quinta Heeren | Barrios Altos | Originally named after the nearby church of the same name, it is named after Óscar Heeren. From 1901 to 1940, the quinta was the headquarters of the embassies of Japan, Belgium, Germany, France and the United States.[34] |  |

| Royal Hospital of Saint Andrew | Jr. Huallaga 846 | The first hospital in both the country and South America,[35] it is also linked to the National University of San Marcos and its early history of healthcare studies in Peru, and once housed a number of mummies of the Inca Empire's nobility, including that of Pachacuti.[35] |  |

| Sanctuary and Monastery of Las Nazarenas | Av. Tacna & Jr. Huancavelica | The complex was built during the 18th century after the original building had to be demolished as it was irreparably damaged during the earthquake of 1746. It is the location of the Lord of Miracles, an icon venerated by local Catholics during festivities that take place every October. |  |

| Sanctuary of Saint Rose of Lima | Av. Tacna | Inaugurated in 1992, it's located in the remains of Saint Rose of Lima's house, including the well used by her family. It is therefore also the location of the miracles attributed to her. |  |

| Stone of Taulichusco | Pasaje Santa Rosa | Since 1985, the stone serves as a memorial to Taulichusco, the last Kuraka of Rímac Valley prior to the arrival of the Spanish. |  |

| Teatro Colón | Plaza San Martín | Its construction began in 1911, being inaugurated on January 18, 1914. Until the 1980s, the theatre functioned normally until it became and started airing adult films, being ultimately closed in 2000. Five years later, an NGO aimed at rehabilitating the building began operating. |  |

| Torre Tagle Palace | Jr. Ucayali 363 | Built during the early 18th century using materials from Spain, Panama and other Central American countries,[36] it was purchased by the government in 1918 and currently serves as the main headquarters of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. |  |

| University of San Marcos Campus and adjacent park | Av. Colmena 1222 | Formerly a Jesuit novitiate, the building and park are the property of the University of San Marcos, where its cultural centre and crypt are located. The park was built in 1870, with a clock tower being built by the German colony as part of the centennial celebrations in 1921. At noon, their bells play notes of the national anthem. |  |

| University of San Marcos' Royal College | Jr. Andahuaylas 348 | Formerly known as Royal College of San Felipe, it dates back to the Spanish era, having housed a military barracks and an art school before currently housing three departments of the university. |  |

| Walls of Lima | Parque de la Muralla | Formerly surrounding what is now known as the Cercado de Lima, a few remains can be seen at the park that runs alongside the Rímac River. | |

Landmarks included within the buffer zone of the World Heritage Site

| |||

| Casa Matusita | Av. Inca Garcilaso de la Vega 1390 | Dating back to the Spanish era, the house is reportedly haunted, although some conspiracy theories suggest that these urban legends were disseminated by the CIA to prevent the building's use for espionage, due to the fact that the U.S. embassy was located across the street at the time. |  |

| Church of Saint Catherine of Siena | Barrios Altos | The church's construction dates back to 1589, when attempts were made by María de Celis to establish a monastery by requesting a licence which was granted but did not materialise due to her death. Her efforts were continued by Saint Rose of Lima starting in 1607, with the complex completed in 1624, some years after her death. |  |

| Cuartel Barbones | Barrios Altos | Originally located next to the city gate named after it, it was originally established as an Indian hospital of the Bethlehemite Brothers that was destroyed during the earthquake of 1687. After independence, it was repurposed into a military barracks. | — |

| Fort of Santa Catalina | Jr. Inambari 790 | The fort is one of the few remaining examples of military viceregal architecture that continues to exist in Peru. Built at the beginning of the 19th century, it served as the barracks for the artillery units of the army and the police forces. |  |

| Mogrovejo Hospital | Jr. Áncash 1271 | Founded in the viceregal era with a Royal Decree of August 26, 1700, as the "Refuge for Incurables", it is currently an institute for neurology and features a museum dedicated to the human brain. |  |

| Plaza Dos de Mayo | The square was built in 1874 by the Peruvian government to commemorate the Battle of Callao, which took place off the coast of Callao on May 2, 1866, between the navies of Peru and Spain. It serves as the intersection of Colonial, Alfonso Ugarte and Colmena avenues. |  | |

Ancient Reduction of Santiago Apostle of Cercado[edit]

The Ancient Reduction of Santiago Apostle of Cercado (10.2 ha) was added to the World Heritage Site in 2023.[2]

| Name | Location | Notes | Photo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alipio Ponce Vásquez Police School | Av. Sebastián Lorente 769 | Founded in the Quinta Cortés as a mental hospital that operated between 1859 and 1918, it was repurposed as a training academy for the Civil Guard, and continues to be used by the National Police of Peru. |  |

| Bastión de Santa Lucía | Jr. José de la Rivera & Dávalos 491-499 | One of the few remains of the walls of Lima, preserved better than the other remains.[37] | — |

| Cinco esquinas (partial) | In the 19th century, it was a place where Lima's bohemians gathered, becoming a refuge for criminals the following century.[38] It is located at the intersection of Junín, Miró Quesada and Huari streets. It inspired Mario Vargas Llosa's novel of the same name.[39] | — | |

| Santiago Apóstol del Cercado | Jr. Conchucos 720 | Rebuilt after the 1746 earthquake, the barroque church was again affected by the 1940 Lima earthquake, being restored by Emilio Harth-Terré and Alejandro Alva. A figure of the Virgin of Carmel was enshrined in the church during a ceremony attended by then president Augusto B. Leguía on July 16, 1921.[40] |  |

| Plazuela del Cercado | Originally an Indian reduction,[b] it is unique in the continent, as it has a rhomboid shape.[42] | ||

| Santo Cristo de las Maravillas | Av. Sebastián Lorente & Jr. Áncash | Named after the devotion of the same name,[43] it was originally located in front of one of the city gates, which took its name from the church.[44] It was the old starting point for funeral processions to the General Cemetery of Lima, given its location, which precedes the cemetery's foundation in 1808.[43] |  |

Quinta and Molino de Presa[edit]

The Quinta and Molino de Presa (1.62 ha) were added to the World Heritage Site in 2023.[2]

| Name | Location | Notes | Photo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quinta and Molino de Presa | Jr. Chira 344[45] | The 18th century building was built under the government of then viceroy of Peru, Manuel de Amat y Junyent. It comprises a constructed area of 15,159 square metres (163,170 sq ft).[46] |  |

| Callejón de Presa | A passage and street that leads to the Quinta.[47] | — | |

| Plazuela de Presa | The public square outside the Quinta.[48] | — | |

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ PROLIMA member Juan Miguel Delgado explains that, although the emblem used by the Blue Shield International (officially represented in Peru by the Comité Peruano del Escudo Azul Peruano since January 30, 2019) is a blue-and-white shield, a different colour was specifically chosen to contrast with the buildings' façades, with black serving as a neutral alternative to the stardard navy blue.[3]

- ^ A population centre in which dispersed indigenous people were grouped, for the purposes of evangelisation and cultural assimilation.[41]

References[edit]

- ^ "Centro Histórico de Lima: Patrimonio Mundial". Sitios del Patrimonio Mundial del Perú.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Historic Centre of Lima". World Heritage Convention. UNESCO.

- ^ Tolentino, Scheila (9 May 2023). "Centro de Lima: ¿por qué algunas edificaciones tienen un escudo blanco y negro? Esta es la razón". La República.

- ^ Martínez Hoyos, Francisco (15 March 2018). "Lima, la joya del virreinato del Perú". La Vanguardia.

- ^ "Centro Histórico de Lima Patrimonio Cultural". UNESCO Cátedra. Universidad de San Martín de Porres.

- ^ Pereyra Colchado, Gladys (27 September 2020). "Los secretos de una Lima subterránea y su relación con el hallazgo en la plazuela San Francisco". El Comercio.

- ^ Augustin, Reinhard (2017). El Damero de Pizarro: El trazo y la forja de Lima (PDF) (in Spanish). Lima: Municipality of Lima. ISBN 978-9972-726-13-2. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^ "Presidenta Boluarte destaca ley que crea régimen especial del Centro Histórico de Lima". El Peruano. 17 January 2024.

- ^ Calidad en el Museo Palacio Arzobispal (PDF) (in Spanish). Universidad Ricardo Palma. 2017. pp. 7, 17.

- ^ Fhon Bazan, Miguel (12 December 2016). "La antigua Iglesia de Nuestra Señora de los Desamparados". Medium.com. Cultura Para Lima.

- ^ a b Garay, Karina (28 July 2023). "Fiestas Patrias: estas son las 4 plazas de Lima donde se gritó la Independencia".

- ^ Salmón Salazar, Gisella (1 February 2010). "Cinco Siglos de Historia: Casa de Aliaga" (PDF). Variedades. pp. 2–4.

- ^ Orrego Penagos, Juan Luis (16 July 2011). "Las antiguas calles de Lima". Blog PUCP.

- ^ Salas Pomarino, Jimena (23 March 2020). "Casa de Divorciadas: retorno a la belleza". Revista COSAS.

- ^ Planas, Enrique. "Las casonas del Centro de Lima". El Comercio.

- ^ "La jornada de la "toma de Lima" termina con enfrentamientos y el incendio en un edificio en el centro histórico de la capital peruana". BBC Mundo. 20 January 2023.

- ^ Llerena, Paula; Pacheco Ibarra, Juan José (20 January 2023). "¿Cuál es la historia detrás de la casona que se quemó y derrumbó durante las protestas en Lima?". Trome.

- ^ "La casona más antigua de Lima". El Peruano. 19 November 2017.

- ^ Fangacio Arakaki, Juan Carlos (10 March 2018). "Balcones de Lima: levantar la mirada a la tradición". El Comercio.

- ^ Bromley Seminario, Juan (2019). Las viejas calles de Lima (PDF) (in Spanish). Lima: Metropolitan Municipality of Lima. p. 382.

- ^ Víctor Angles Vargas (1983). Historia del Cusco Colonial. Vol. II. Lima: Industrialgrafica .S.A. p. 742.

- ^ García, Miguel (29 September 2021). "Criptas y catacumbas en Palacio de Gobierno: los misterios de los túneles que se mostraron en 1981". El Comercio.

- ^ a b "Catacumbas: el cementerio colonial de Lima revela sus misterios". RPP Noticias. 25 October 2016.

- ^ "Perú: Catacumbas bajo Iglesias barrocas". Euronews / AFP. 18 April 2022.

- ^ Espinoza, Carlos; Niño, Mauricio (24 February 2020). "Semana Santa: recorrido virtual por las iglesias del Perú y del mundo". El Comercio.

- ^ "Catálogo. Martínez Montañés". Andalucía y América. Proyecto Mutis.

- ^ Bonilla Di Tolla, Enrique (2009). Lima y el Callao: Guía de Arquitectura y Paisaje (PDF) (in Spanish). Junta de Andalucía. pp. 173–174.

- ^ "Municipio de Lima realiza obras de recuperación en histórica iglesia de La Recoleta". Andina. 2 March 2023.

- ^ Ardiles, Abby (21 May 2022). "Edificio Giacoletti: ¿Cuáles son los planes de la municipalidad para poder restaurarlo?". El Comercio.

- ^ García Bendezú, Luis (27 May 2014). "Historia de la vieja sede del Ministerio de Educación". El Comercio.

- ^ Gonzales Obando, Diana (23 June 2020). "Hotel Comercio: A 90 años del sanguinario crimen que escandalizó la Lima de los años treinta". Perú 21.

- ^ Angulo, Jazmine (18 January 2024). "Bar Cordano en el Centro de Lima: un tesoro gastronómico impregnado de historia y tradición". Infobae.

- ^ "Santa Rosa de Lima: conoce los lugares turísticos que te cuentan su vida". El Comercio. 30 August 2022.

- ^ Cayetano, José (19 June 2023). "El prometido regreso a la vida de tres casonas históricas de Lima". El Comercio.

- ^ a b "La historia de San Andrés, el hospital más antiguo del Perú en donde se halló un cementerio colonial". La República. 3 November 2022.

- ^ "Historia del Palacio de Torre Tagle". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Peru. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012.

- ^ Cubillas Soriano, Margarita (1993). Guía histórica, biográfica, e ilustrada de los monumentos de "Lima metropolitana" (in Spanish). p. 37.

- ^ Cueto, Alonso (4 March 2016). "Intersecciones del tiempo". El País. ISSN 1134-6582.

- ^ Blanco Bonilla, David (23 March 2016). "De Miraflores a Cinco esquinas, la Lima de Vargas Llosa". La Vanguardia.

- ^ "Iglesia Santiago Apóstol del Cercado". Medium.com. Cultura Para Lima. 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Reducción". Diccionario de la lengua española (in Spanish) (23rd ed.). Real Academia Española. 2014.

- ^ "Plazuela de Cercado y alrededores". Medium.com. Cultura Para Lima. 27 August 2018.

- ^ a b "Turismo en Iglesia de Santo Cristo de Las Maravillas". Turismoi.pe.

- ^ Bromley Seminario, Juan (2019). Las viejas calles de Lima (PDF) (in Spanish). Lima: Metropolitan Municipality of Lima. pp. 60–61.

- ^ Gamarra Galindo, Marco (13 January 2010). "De visita por la Quinta de Presa". El Comercio.

- ^ "Quinta Presa". Ministerio de Comercio Exterior y Turismo del Perú.

- ^ Gamarra Galindo, Marco (4 March 2010). "Quinta Presa: un palacio en el Rímac". Blog PUCP.

- ^ Pastorelli, Giuliano (27 October 2011). "Ganadores del Concurso de Tratamiento para el Espacio Público El Rímac". ArchDaily.